A philological exegesis of verse 2:183 of the Qur’ān.

A philological exegesis of verse 2:183 of the Qur’ān.

When one hears of fasting in the context of religious observance it could be said with little argument that the first thing to pop into one’s mind would be Islam. There is no question that our dear friends from the Christians and the Jews observe fasting to varying degrees. Yet, the rigorous fasting of Ramaḍān has made Muslims identifiable as those who enjoin fasting as a pillar of their faith.

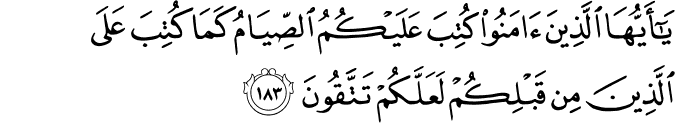

When fasting was first ordained upon the Muslims, God revealed the following words of the Qur’ān:

“O you who believe! Fasting has been ordained upon you as it was ordained upon those before you, in the hope that you might become ever conscious of God.” ((The Holy Qur’ān, Surat al-Baqara 2:183))

“O you who believe! Fasting has been ordained upon you as it was ordained upon those before you, in the hope that you might become ever conscious of God.” ((The Holy Qur’ān, Surat al-Baqara 2:183))

This verse’s meaning, though quite clear, is deep beyond measure and has therefore been subject to much analysis by the exegetes of the Qur’ān for a millennium and a half. What is the origin and true meaning of the word ṣawm for fasting? Who are those who preceded the Muslims in fasting as a religious duty as mentioned in this verse? What does God mean by “in the hope that you might become ever conscious of God?”

Ṣiyām: Its meaning and Semitic cognates

This first part of this verse is transliterated: “yā ayyuh-alathīna āmanū kutiba `alaykum al-ṣiyām.”

The word ṣiyām, being the verbal noun, or maṣdar in Arabic morphology, is derived from the root ṣawm. From Ṭabaristan neighboring the Caspian Sea, the famed Qur’ānic exegete of the 9th Century CE, Abu Ja`far Muḥammad ibn Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, stated:

فُرِضَ عَلَيْكُمُ الصِّيَامُ، وَالصِّيَامُ مَصْدَرٌ مِنْ قَوْلِ الْقَائِلِ: صُمْتُ عَنْ كَذَا وَكَذَا، يَعْنِي كَفَفْتُ عَنْهُ…

“[It means] fasting (al–ṣiyām) has become obligatory (furiḍa) upon you. And al-ṣawm is the verbal noun as exemplified in the statement: ‘I abstained (ṣumtū) from such and such,’ meaning ‘I desisted from it.’

He further cites in the Qur’ān an example of this word usage to mean guarding the mouth, not just from food and drink, but from speech:

وَمِنْهُ قَوْلُ اللَّهِ تَعَالَى ذِكْرُهُ {إِنِّي نَذَرْتُ لِلرَّحْمَنِ صَوْمًا} [مريم: 26] يَعْنِي صِمْتًا عَنِ الْكَلَامِ

“And, similarly, God the Most High has said [quoting Mary], ‘Verily, have I pledged on oath of abstinence to the Merciful God..’ [Maryam 19:26] meaning abstinence from speech.’

The German Semitic linguist and Biblical textual critic of the early 19th Century CE, Friedrich Wilhelm Gesenius, ((Heinrich Friedrich Wilhelm Gesenius [b. February 3, 1786 – d. October 23, 1842])) concurs with this understanding of this word’s cognate in Hebrew with additional detail:

“צוּם To fast. (Arabic صام Aram. id. ((“Aramaic Idiom”)) The primary idea lies in the mouth being shut; see as to roots ending in m above at דָמַם page CCIII, B.) Judges 20:26, Zechariah 7:5 הֲצוֹם צַמְתֻּנִי ‘have ye fasted to me?’ where the suffix must be regarded as a dative. Hence –

צוֹם m. fasting, a fast, 2 Samuel 12:16. Plural צוֹמוֹת Esther 9:31.” ((Hebrew-Chaldee Lexicon to the Old Testament, Gesenius, p.705))

In regards to Gesenius’ reference to “roots ending in m…at דָמַם” we find an interesting reference that ties back to the previously mentioned verse in Chapter of Mary in the Qur’ān. Gesenius states:

“Followed by ל to keep silence for someone, i.e. to hear someone without speaking. Hence, דָּמֵם לַיהוָֹה to be silent for Jehovah; i.e. patiently and with confidence to expect his aid, Ps[alms] 37:7; 62:6..”

So the aforementioned phrase, dawm la-Yahweh, meaning “Be silent for God”, bears an uncanny syntactical resemblance to Mary’s statement in the Qur’ān, innī nadhartū li-Rahmāni ṣawm-an, meaning, “I have pledged an oath of silence to the Merciful God.” It is a testimony to the lexical consistency between the Qur’ān and the language of the previous Prophets.

Of further interest is that in early Semitic languages, a terminal letter mīm (מ) was an onomatopoeia meaning to imitate the sound of a shut mouth indicating silence and fasting:

“This root is onomatopoetic, and one which is widely sprad in other families of languages, and equally with the kindred roots הָמָת, הוּם, הָמָם, and Gr[eek] μύω , it is the imitation of the sound of the shut mouth (hm, dm). Its proper meaning therefore, is to be dumb, which is applied both to silence and quietness, and also to the stupefaction of one who is lost in wonder and astonishment…” ((Ibid. p. 203))

Out of the Biblical verses cited by Gesenius, the most relevant to this discussion is Zechariah 7:5:

אֱמֹר אֶל-כָּל-עַם הָאָרֶץ, וְאֶל-הַכֹּהֲנִים לֵאמֹר: כִּי-צַמְתֶּם וְסָפוֹד בַּחֲמִישִׁי וּבַשְּׁבִיעִי, וְזֶה שִׁבְעִים שָׁנָה-הֲצוֹם צַמְתֻּנִי, אָנִי

“Say to all the people of the land, and to the priests: ‘When you fasted and mourned in the fifth and seventh months during those seventy years, did you really fast for Me–for Me?

The Prophet Muḥammad ((Peace and blessings be upon him.)) related the following statement from God:

الصيام لي وأنا أجزي به والصائم يفرح مرتين عند فطره ويوم يلقى الله

“Fasting is for Me, and I reward it accordingly. There are two moments of joy for the fasting person: Once when they break their fast and the other on the Day they meet God.” ((Sunan al-Nasā’ī, The Book of Fasting, vol. 4))

As it was ordained upon those before you…

Renowned student of Imām Aḥmad’s son, Ṣāliḥ, and exegete of the Qur’ān, Ibn Abī Ḥātim, ((`Abd al-Raḥmān bin Muḥammad bin Idrīs al-Rāzī (d. 938 CE) – See Ṭabaqāt al- Ḥanābila, Abu Ya`la )) relates:

عَنِ ابْنِ عَبَّاسٍ فِي قَوْلِهِ: {كُتِبَ عَلَيْكُمُ الصِّيَامُ كَمَا كُتِبَ عَلَى الَّذِينَ مِنْ قَبْلِكُمْ} [البقرة: 183] يَعْنِي بِذَلِكَ «أَهْلَ الْكِتَابِ» وَرُوِيَ عَنْ عَطَاءٍ الْخُرَاسَانِيِّ، وَالشَّعْبِيِّ، وَالسُّدِّيِّ نَحْوُ ذَلِكَ

“Ibn `Abbās said in regards to who is referred to in the Divine statement {Fasting has been ordained upon you as it was ordained upon those before you..} [al-Baqarah 2:183] , ‘It refers to the People of the Book.’ This has also been reported from `Atā’ al-Khorasānī, al-Sha`bī, al-Suddī and others.”

Likewise, after reviewing the opinions of various Companions of the Prophet and their students, al-Ṭabarī states:

وَأَوْلَى هَذِهِ الْأَقْوَالِ بِالصَّوَابِ قَوْلُ مَنْ قَالَ: مَعْنَى الْآيَةِ: يَا أَيُّهَا الَّذِينَ آمَنُوا فُرِضَ عَلَيْكُمُ الصِّيَامُ كَمَا فُرِضَ عَلَى الَّذِينَ مِنْ قَبْلِكُمْ مِنْ أَهْلِ الْكِتَابِ

“The preponderant and correct opinion from these is the one that says the meaning of the verse is: O you who believe! Fasting has been made a duty upon you, just as it was made a duty upon those before you from the People of the Book.” The term “People of the Book” is a Qur’ānic reference to the Jews and the Christians.

The Prophet Jonah is best known for languishing in the belly of a whale for three days and three nights because he did not follow God’s instructions to call upon the people of Nineveh. Nineveh were enemies of Israel so, using his own judgment, he figured the people of Spain would be more suited for God’s message. Little did Jonah realize that God sent him to Nineveh specifically so that they might be saved from an imminent destruction. After Jonah was released from the whale’s belly and realized his mistake, he fulfilled the order of his Lord calling them to fast 40 days in hopes that God might save them.

“Now the word of the Lord came to Jonah the second time, saying, ‘Arise, go to Nineveh, that great city, and preach to it the message that I tell you.’ So Jonah arose and went to Nineveh, according to the word of the Lord. Now Nineveh was an exceedingly great city, a three-day journey in extent. And Jonah began to enter the city on the first day’s walk. Then he cried out and said, ‘Yet forty days, and Nineveh shall be overthrown!’ So the people of Nineveh believed God, proclaimed a fast, and put on sackcloth, from the greatest to the least of them. Then word came to the king of Nineveh; and he arose from his throne and laid aside his robe, covered himself with sackcloth and sat in ashes. And he caused it to be proclaimed and published throughout Nineveh by the decree of the king and his nobles, saying, Let neither man nor beast, herd nor flock, taste anything; do not let them eat, or drink water. But let man and beast be covered with sackcloth, and cry mightily to God; yes, let every one turn from his evil way and from the violence that is in his hands. Who can tell if God will turn and relent, and turn away from His fierce anger, so that we may not perish? Then God saw their works, that they turned from their evil way; and God relented from the disaster that He had said He would bring upon them, and He did not do it.” ((Jonah 3:1-10))

There is a textual discrepancy between the Hebrew text and the Greek Septuagint in that the Septuagint uses the word three instead of forty. The famed British Methodist theologian of the early 19th Century CE, Adam Clarke states:

“Both the Septuagint and the Arabic read three days. Probably some early copyist of the Septuagint, from whom our modern editions are derived, mistook the Greek numerals μ (forty) for γ (three); or put the three days’ journey in preaching instead of the forty days mentioned in the denunciation. One of Kennicott’s MSS, instead of ארבעים arbaim, forty, has שׁלשׁים sheloshim, thirty: but the Hebrew text is undoubtedly the truth reading; and it is followed by all the ancient Versions, the Septuagint and Vulgate excepted.” ((The Holy Bible, with a Commentary and Critical Notes, Adam Clarke, p. 3344))

Aside from the fact that the month long fast saved Nineveh from destruction —and it may have been a true thirty days according to some Hebrew manuscripts— what is interesting to note is that they were commanded to all wear a sackcloth so that the king and his subjects, the rich and the poor, would all be equal before God and one another. The only place we see this as an institution today is at the Ka`bah in the city of Mecca where all are commanded to wear a simple white cloth, nary a stitch, the prince indistinguishable from the pauper.

When looking into the Bible, one sees that fasting was a means of atonement and redemption for the masses, but for the Prophets it was a fortification of their spiritual mettle when communing with God or doing battle with Satan. For it was a forty day fast that prepared Moses ((Peace and blessings be upon him.)) to receive no other than the Ten Commandments:

“So he was there with the Lord forty days and forty nights; he neither ate bread nor drank water. And He wrote on the tablets the words of the covenant, the Ten Commandments.” ((Exodus 34:28))

There are at least three separate occasions recorded in the Old Testament wherein Moses fasted for forty days as seen in Deuteronomy, Chapter 9:

“And I fell down before the Lord, as at the first, forty days and forty nights; I neither ate bread nor drank water, because of all your sin which you committed in doing wickedly in the sight of the Lord, to provoke Him to anger.” ((Deuteronomy 9:18))

In 1 Kings we find a month long fasting conducted by the Prophet Elijah:

“So he arose, and ate and drank; and he went in the strength of that food forty days and forty nights as far as Horeb, the mountain of God. And there he went into a cave, and spent the night in that place; and behold, the word of the Lord came to him, and He said to him, ‘What are you doing here, Elijah?’ So he said, ‘I have been very zealous for the Lord God of hosts; for the children of Israel have forsaken Your covenant, torn down Your altars, and killed Your prophets with the sword. I alone am left; and they seek to take my life.’” ((1 Kings 19:8-10))

Similarly, in the Gospels we find a forty day fast exclusive to Jesus Christ ((Peace and blessings be upon him.)) in order to prepare him to face the temptations of Satan:

“Then Jesus was led up by the Spirit into the wilderness to be tempted by the devil. And when He had fasted forty days and forty nights, afterward He was hungry.” ((Matthew 4:1-2, with similar accounts in Mark 1:13, Luke 4:2))

In the Peshitta, we find the Syriac for “fasted forty days and forty nights” as:

![]() w-ṣam arba`īn yawmīn w-arba`īn laylawn..

w-ṣam arba`īn yawmīn w-arba`īn laylawn..

In this verse the perfect singular 3rd Person masculine verb is employed from the same root of ṣawm used consistently in the Bible.

However, Jesus did not command this rigorous month long fast upon his disciples. It was exclusive to him. It is related in the Gospels that during a feast with some tax collectors, the Pharisees asked Jesus why, in spite of John the Baptist and his followers fasting frequently, the Disciples of Christ were eating and drinking. To this Jesus replied, “Can you make the guests of the bridegroom fast while he is with them? But the time will come when the bridegroom will be taken from them. In those days they will fast.” ((Luke 5:34-35))

In those days they will fast. The proverbial “bridegroom” was none other than Christ himself and the “guests” were obviously his disciples. Christ was foretelling of the soon approaching time when he would be taken away from them. The parable Christ relates in the next two verses, explaining why he did not enforce fasting upon his disciples, is of the utmost relevance:

“No one tears a patch from a new garment and sews it on an old one. If he does, he will have torn the new garment, and the patch from the new will not match the old.” ((Luke 5:36))

Fasting is of the “new garment”. His disciples were of the “old one”. Applying the “new garment” to the “old” garment would be a jurisprudential anachronism. After Christ was taken away from the world, then was fasting to become law. That will be the “new garment” which they were, at that time, not yet to bear.

Most scholars concur that Christ most definitely knew Hebrew for liturgy. There is some debate as to whether he was familiar with Greek, and possibly Latin, due to the political climate of Palestine in his lifetime. Yet, his vernacular would have most certainly been Aramaic. ((An Aramaic Approach to the Gospels and Acts, Matthew Black, Oxford: Clarendon Press 1946, 1967)) Specifically, he would have spoken the Galilean and/or Old Judean dialects. Today, no Gospel literature from the 1st Century CE exists in any Semitic language. What we have are later Syriac versions of the Gospels such as the Peshitta and Old Syriac Gospels that date to approximately 5 centuries after Christ, but offer a relatively faithful glimpse into what his words might have been. These Gospels were used as reference when scripting the film “The Passion of the Christ”.

The phrase “In those days they will fast” in the Peshitta is:

![]() haydayn n’ṣawmūn bi-henūn yawmatā

haydayn n’ṣawmūn bi-henūn yawmatā

Note that the word for “fast” in this verse is n’ṣawmūn which is the masculine third person imperfect verb based on the Aramaic lexeme ṣawm for which the masculine singular emphatic noun is ṣawmā. ((A Compendius Syriac Dictionary Founded Upon the Thesaurus Syriacus, R. Payne Smith, p. 475)) This is an identical cognate to the Arabic root for fasting previously discussed.

When Christ was taken up to His Lord, then only would his followers perform the ṣawm. This was a prophecy.

One of the greatest Church Fathers of the first two centuries after Christ was Origen ((Origen Adamantius [b. 184CE – d. 254CE])) of Alexandria to whom can be credited the very existence of the Bible as we know it. Origen relates that the early church enjoined a forty day fast, yet when that forty day fast occurred is unknown.

“Second, in his Homilies on Leviticus Origen refers to various fasting practices in the church of his day, saying: ‘They fast, therefore, who have lost the bridegroom; we having him with us cannot fast. Nor do we say that we relax the restraints of Christian abstinence; for we have the forty days consecrated to fasting, we have the fourth and sixth days of the week, on which we fast solemnly.’ Unfortunately, Origen does not indicate when these forty days of fasting are to take place.” ((The Rites of Christian Initiation: Their Evolution and Interpretation, Maxwell Johnson, Liturgical Press, p. 74))

So we do know that the early Christians fasted for forty days, but we do not know when they fasted. It is likely that the fasting occurred between the Epiphany in January to the Apostle’s Fast and Pentecost in June. All of these were periods of fasting for the early Church, but have largely fallen out of practice amongst the rank and file of the modern Church.

In the hope that you might become ever conscious of God…

The final part of the verse offers hope in a way that most who have not dug deep into the meaning of it will find inspiring.

لَعَلَّكُمْ تَتَّقُونَ

la`allakum tattaqūn..

“In the hope that you might become ever conscious of God.”

The word taqwa is of extremely ancient origin. Perhaps, the earliest record of its usage is in the Assyro-Akkadian name of the extinct city Altaqū as mentioned in inscriptions ((The Cuneiform Inscriptions and the Old Testament, Eberhard Schrader, 1885, pp. 159-160, 285-289, 297-307)) documenting the campaign of the 8th Century BC Assyrian king, Sennacherib, ((Sennacherib, Akkadian – Sîn-ahhī-erība, [705BC – 681BC])) against a crushed Judean rebellion backed by an Egyptian-Babylonion confederacy. The meaning of Altaqū is related by Gesenius to be “to which God is fear, or object of fear”. ((Hebrew-Chaldee Lexicon to the Old Testament, Gesenius, p. 55))

The famed Ḥanbalī theologian, Shams al-Dīn Muḥammad bin Ahmad al-Saffārīnī, says about the word taqwā:

وَالتَّقْوَى لُغَةً الْحَجْزُ بَيْنَ الشَّيْئَيْنِ، وَشَرْعًا التَّحَرُّزُ بِطَاعَةِ اللَّهِ عَنْ مُخَالَفَتِهِ وَامْتِثَالِ أَمْرِهِ وَاجْتِنَابِ نَهْيِهِ

“Linguistically, taqwā refers to a barrier between two things. In Islamic legal understanding, it is the shield against that which goes against God which is found in obedience to Him, submission to His commands, and eschewing what He forbids.” ((Lawāmi` al-Anwār al-Bahīyyah, al-Saffārīnī, p. 53))

The initiating particle la`alla (لعلّ) is unique in that it can express either hope or fear for the addressed. The basic meaning of this particle is “So that...” as the Persian philologist of Nīshapūr, Abū Manṣūr al-Tha`alibī, states:

لعلّ: بمعنى كي كما قال تعالى: {وَأَنْهَاراً وَسُبُلاً لَعَلَّكُمْ تَهْتَدُونَ} 6 يريد كي تهتدوا

“La`alla: it means is ‘so that..’ as God has stated: {..and streams and roads that you might find your way} meaning ‘so that you might find your way.’” ((Fiqh al-Lugha wa Sirr al-`Arabīyya, Abu Mansur al-Tha`ālibī, vol. 1, p. 252))

Yet, there is an additional dimension to its usage and that is to express hope or fear. The famous work of Arabic syntax and grammar, al-Ājarrūmīyyah, states:

ومعنى إنَّ وأَنَّ للتوكيد، ولَكِنَّ للاستِدراك، وكَأَنَّ للتشبيه، وليت للتمَنِّي، ولَعَلَّ للتَّرَجِّي والتَّوَقُّع

“The meaning of inna and anna is emphasis, as for lākinna it is used to correct a preceding statement, ka’anna is used for comparison, layta is used to express an unattainable desire, and la`alla is used for hope and expectation. ((Al-Ājarrūmiyyah, Ibn Ājarrūm, p. 14))

Scholar and Arabic linguist of the 20th Century CE, Muṣṭafā al-Ghalayīnī, states:

ومعنى (لعلَّ) الترجّي والاشفاقُ. فالترجي طلبُ الامرِ المحبوب، نحو “لعلَّ الصديقَ قادمٌ”. والاشفاقُ هو الحذَرُ من وقوع المكروه، نحو “لعلّ المريضَ هالكٌ”. وهي لا تُستعملُ إلاّ في الممكن

“(la`alla) has a meaning of hope and sympathy. Hope such as to desire something for the beloved. For example ‘Perhaps (la`alla), the friend will arrive.’ Sympathy such as to be fearful that some ill should befall them. For example ‘It is possible (la`alla) that the sick person will perish.’ This is not employed unless in the case of the subject’s possibility.” ((Jami` al-Durūs al-`Arabīyya, Shaykh Muṣṭafā al-Ghalayīnī, vol. 2, p. 299))

Thus, we can understand from la`allakum tattaqūn that God is expressing a hope and expectation that by fasting we will reach a level of nearness to Him and achieve Taqwā. The lexical usage requires that this objective of having the ultimate bond and connection to Him, to the point that we are ever conscious of Him, is a very real eventuality. Yet, one may ponder whether it is God or His believer who hopes for that. God has assured us that this is His hope. Now it is up to us to show Him that it is ours.

This is an extraordinary effort. We will be benefitting from this work for years to come.

Jazakallah Khair for this very informative post! I love how the author wrote this post in a very professional and academic manner. I’m sure that Christians and Jews would also be interested in reading this post!

ditto.

Great post excellent knowledge in the Bible!!

Professor Shibli our dear brother multifaceted teacher.

I pray God bless you and protect you and your family!

Shibli, Extra ordinary, out of this world!

Thank you! This article was extraordinary, it should be included in tafasir and interfaith studies/meetings.

Subhanallah! Jazakallahu khair 🙂 I learnt so much!

[…] BY SHIBLI ZAMAN | SOURCE : SUHAIBWEBB […]

[…] “O you who believe! Fasting has been ordained upon you as it was ordained upon those before you, in the hope that you might become ever conscious of God.”1 […]