By Kitty Caparella

SAYFULLAAH Al-Amriykiy was reeling after he read a Daily News story last August about Nasir Daymar Gould, a 30-year-old West Philadelphia native, and five other U.S. citizens locked up for two months in a Yemeni prison.

“I knew exactly what he was going through,” said Al-Amriykiy, 53, a world-renowned jujitsu grand master.

Al-Amriykiy himself had been imprisoned in Yemen. The story about Gould prompted unspeakable flashbacks.

That’s when Al-Amriykiy and two of his martial-arts students – Anwar Whittaker, 25, of West Philadelphia, and Abdul Kareem Wright, 31, of Frankford – felt compelled to warn fellow Muslims of the perils of studying Islam in Yemen.

This two-part story of their harsh experience is based on interviews with all three of the men.

The trio had – like Gould – traveled to Yemen to study Arabic and the Quran. They made their trip in 2001, shortly after 9/11.

They were unexpectedly thrown into Yemen’s Central Prison without charges. They were made to eat putrid food. They feared they would be killed, and that each day would be their last. Finally, their families raised money to free them.

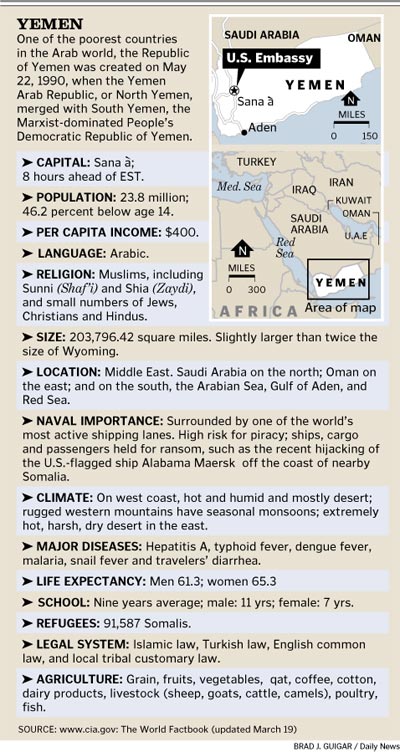

While Yemen officially condemns terrorism, it remains a terrorist hotspot in the Middle East – and one of the poorest countries in the Arab world, with a per capita income of $400 a year.

Last year, Gould was one of 21 Americans locked inside Yemeni prisons, part of the 3,500 U.S. citizens jailed in foreign countries each year.

Christoph Wilcke, a Middle East expert at Human Rights Watch, said that it is not unusual for students of religious studies to be at risk for arrest.

The State Department warns U.S. citizens “to defer nonessential travel” in Yemen.

Al-Amriykiy’s journey to Yemen began in early 2001 with a simple desire to learn more about Islam.

Al-Amriykiy’s journey to Yemen began in early 2001 with a simple desire to learn more about Islam.

He had been an imam – a Muslim cleric – for five years at Al-Dirr-Wat-Taqwa Masjid, a mosque at 52nd Street near Market, just below his third-floor martial-arts studio.

Like many American Muslims, he wanted to know more. He wanted to speak Arabic fluently and to study under one of the most revered Islamic scholars in the Middle East.

His friend, Jauhar Ahmad, a Bangladeshi imam who ran a mosque in Jamaica, Queens, recommended studying under Shaykh Muhammad Al-Imaan, an Islamic scholar at a rural religious camp in Yemen.

Ahmad offered his home in Sana’a, the capital of Yemen, as a place for Al-Amriykiy to stay.

Al-Amriykiy didn’t expect problems. He followed the news, but understood that Yemen and the U.S. were cooperating in a joint investigation of the 2000 bombing of the USS Cole, in Yemen, which killed 17 American sailors.

Al-Amrikiy’s excitement about his trip was so contagious that Whittaker and Wright, two of his martial-arts students at Warrior Within Dojo Studio, wanted to go, too. For months, they saved money and planned the trip.

By early September, the trio had obtained 30-day visas to Yemen.

Whittaker, an 18-year-old graduate of West Philly High, had quit his $600-a-week job selling cars in the suburbs. And 24-year-old Wright, a 1995 grad of Kensington High, had left his job cleaning movie theaters.

Then, fate intervened – 9/11. Three days before their flight, terrorists hijacked four planes and crashed them into the World Trade Center, the Pentagon and a field in rural Shanksville, Pa., killing nearly 3,000 people.

The trio were distraught over the incident. Their dream was on hold. But they were so excited about their trip, they ignored official and friends’ warnings to delay it further.

On Sept. 22, 2001, they landed at Sana’a International Airport. In customs, Yemeni authorities tried to send them back. However, Ahmad, who was already in Yemen, paid a $750 bribe to admit them into the country, said Al-Amriykiy.

The culture and living conditions were a shock to the three Philadelphians.

Whittaker felt so uncomfortable that he wanted to return home immediately, but no flights were available.

His braided-corn row hairstyle stunned locals, who called him a girl, he said. Whittaker said a child pointed at him, and yelled: “Anta Yahud” – “You’re a Jew.”

On the morning of Oct. 13, 2001, Al-Amriykiy and Whittaker decided to hike a nearby mountain. They set off at 6:30 a.m. to get a panoramic view of Sana’a. Wright, a North Philadelphia native, was too sick to go.

While climbing, the two saw a shepherd pass them and an elderly woman tending a flock of animals. Then they noticed a bunker on top of the mountain.

An old man called for them to come down. At the foot of the mountain, three men pointed AK-47s at the Americans and pushed the petrified men to the middle of a field.

“I thought they were going to shoot us with the AK-47s,” said Al-Amriykiy.

The jujitsu master calculated how to take on two gunmen so Whittaker could escape, even though he knew he’d be killed by the third.

Suddenly, the old man shouted Arabic at the gunmen, who relaxed. The gunmen took the Americans to two locations where they were repeatedly interrogated. At the second stop, a colonel tried unsuccessfully to reach Ahmad, their Bangladeshi friend, to vouch for them.

Four armed guards then drove them to Yemen’s intelligence agency, the Political Security Organization (PSO), described recently by the Fund for Peace as “a haven for Islamic militants associated with al Qaeda.” The agency answers directly to Yemeni President Ali Abdallah Salih.

Inside the PSO, Al-Amriykiy passed a room with blood-splattered walls, where cables attached to batteries sat on a bloody floor.

“I thought they were going to torture us,” he said.

Instead, the men were led, one at a time, to the nearby Central Prison. A gunman repeatedly poked Al-Amriykiy with a rifle, told him not to turn around, and struck him with his weapon when he did.

In a huge yard separating the PSO from the prison, Al-Amriykiy was blindfolded and ordered to stand against the prison wall. He feared he was about to die.

An official, sitting at a desk in the courtyard, ordered him to remove his blindfold and stare at a camera videotaping him.

Then the official shouted the same questions repeatedly:

Who are you? What agency sent you? Your occupation? What are your parents’ names? When did you arrive?

Hours after standing and answering the same questions, he was taken below ground to what looked like a dungeon. Al-Amriykiy was questioned again, by a colonel. He even offered the prisoner hard bread, but when the colonel bit into it, one of his teeth fell out.

Al-Amriykiy had no idea what had happened to Whittaker, and the colonel wouldn’t tell him.

“No one knew where we were,” said Al-Amriykiy. “I thought, ‘I’m going to be here for the rest of my life,’” I was worried about my pregnant wife. I thought I was never going to see my family again.”

Silently, Al-Amriykiy prayed: “Oh God, if that’s what you have for me, I accept it.”

The next morning, Whittaker, imprisoned in another section of the dungeon, asked to use the bathroom. A guard gave him an assigned time, 8 a.m. Prisoners could only use the toilet three times a day and shower once.

“I can’t live like this,” he thought. He had never been arrested, let alone jailed. Yet the 6-foot-1 teen began plotting how to overtake the much-shorter guards.

“A guard grabbed my arm, I snatched it back. That’s when I lost it,” said Whittaker, recalling his frenzied raving and crying.

Suddenly, a guard showed up at Al-Amriykiy’s cell as he lay on a thin mattress on the stone floor.

“Come,” urged the guard in Arabic.

“I’m thinking, ‘Oh my gosh, something happened to Anwar,’ ” said Al-Amriykiy. “I see six guys with sticks. Anwar’s frantic, screaming, he’s not going into the cell. He was scared. He broke down crying. The guards didn’t know what to do.”

Al-Amriykiy looked into Whittaker’s windowless cell. It was the size of a small closet with a single bulb. The wall was smeared with feces and “stuff written in blood, like somebody was counting,” he added.

He asked a guard if he could get the other guards with sticks to back off, so he could talk to Whittaker, who feared he was about to be killed.

Then, Al-Amriykiy asked the guards if Whittaker could stay with him. His cell, at least, had a window.

Al-Amriykiy wanted to keep the worried teen’s mind occupied. They recited the Quran. They practiced jujitsu.

The next morning, the two were fed the same kind of hard bread that cost the colonel a tooth. They called it “rock” bread. Later that day, they were given slimy rice and okra, a menu that was repeated daily.

“We had nothing to drink but stagnant water” in a filthy soda bottle, said Whittaker.

The teen became sick, bent over in pain with severe dysentery. Once in the bathroom, he wouldn’t leave. A guard asked Al-Amriykiy to get his friend.

“He probably needed a doctor,” said Al-Amriykiy.

He asked the guard to allow Whittaker the time he needed because he was ill.

Whittaker stopped eating for days.

They feared this was it. They would die in the dungeon, and their families would never know.

Part Two:

As 2 gained freedom in Yemen, 3rd lost it

IN FALL 2001, Patricia Johnson, a legal attache with the U.S. Embassy in Yemen, arrived at that nation’s Central Prison to check on two jailed Philadelphians – and to deliver a warning.

A week earlier, Sayfullaah Al-Amriykiy, an imam at a mosque at 52nd Street near Market, and his martial-arts student Anwar Whittaker, had hiked up a mountain and were taken into custody by the military without charges.

The two had traveled to Yemen with another Philadelphian, Abdul Kareem Wright, to study Arabic and the Quran at an Islamic camp in Marba’. The camp had been recommended by a friend – but they were ensnared in the intrigue that followed the 9/11 terror attacks in the U.S.

At the prison meeting, Johnson warned Yemeni Col. Mohammed Ali, who had interrogated the Americans, and other officials that Al-Amriykiy was a renowned karate sensei, or teacher, who was on the U.S. team that won the World Cup in Panama in 1994.

Yemeni officials gasped.

The accolade was intended both to impress the captors – and to warn them that the United States was monitoring the American prisoners’ treatment.

Later, the colonel asked Al-Amriykiy, who was imprisoned in a below-ground dungeon: “Are you all right?”

“You didn’t put me in here. God put me in here,” Al-Amriykiy told him. “God will get me out. You can’t help me.”

The puzzled colonel asked: “Why do you talk like this?”

In her next visit, Johnson asked the colonel if she could give Al-Amriykiy and Whittaker 5,000 riyals of Yemeni currency – about $25 – to buy food.

Guards, however, charged a “fee” – three times the cost of the food – to bring it in. The two Americans asked for chicken and rice, grapes and cartons of juice.

The night of the pair’s arrest in Sana’a, Yemen’s capital, their friends, Wright and Jauhar Ahmad, a Bangladeshi imam who ran a mosque in Jamaica, Queens, became frantic looking for them.

Finally, Ahmad paid for information to find them. He learned that Yemen’s intelligence agency, the Political Security Organization (PSO), wanted money for their release. Thus began negotiations. Each man’s family was forced to raise $2,500. Ahmad paid $5,000 to the PSO.

None of the Americans had ever been arrested in the United States. But they quickly learned firsthand about political graft in Yemen that would be documented in an investigation by an outside agency seven years later.

The annual report of the Fund for Peace last year described corruption at every level and branch of the Yemeni government, particularly with the police, who were responsible for “arbitrary arrests, torture and murders,” and horrible prison conditions.

“Police often bargain directly with families and tribesmen concerning the release of prisoners,” according to the report.

Al-Amriykiy had another word for the bargaining: “extortion.”

The U.S. Department of State has long warned Americans to avoid nonessential travel to Yemen, one of the poorest and most terror-plagued nations in the world – a warning that the three Philadelphians in their zeal to learn more about Islam did not heed.

After 14 days lying on the dungeon’s cold stone floor, and the bribe payment, Al-Amriykiy and Whittaker were released. Col. Ali asked for their e-mail addresses. Johnson and a Yemeni translator who worked for the U.S. embassy invited the two to lunch. Al-Amriykiy asked Johnson for a letter of explanation from the embassy and sought a letter of apology from Yemeni officials.

Johnson agreed to give him a letter saying that they were jailed wrongly, but she advised him that the Political Security Organization would never admit it had made a mistake, he said.

In Sana’a, the two had a brief reunion with their friends Wright and Ahmad while preparing to return to the United States.

Despite what had happened, Wright decided to stay. He set off alone to the rustic Islamic camp in Marba’. At the camp administration office, he was required to turn in his passport.

For five weeks, Wright lived in nearly primitive conditions with 30 men, one hot plate and no bathroom in a dorm. Given a bucket, he filled it daily to wash himself and used an outhouse, as the weather turned cold in late fall. Hot water was available only on Fridays.

He ate meat or chicken only once a week – Fridays – and dropped 25 pounds, down to 170 on his 6-foot-1 frame.

With so little distraction, he said, “I was getting on a roll, learning Arabic with a private teacher, and studying the Quran in Arabic.”

Each day, he prayed five times – from before sunrise to nightfall. He memorized a part of the Quran. At 10 a.m., he studied Arabic with a private tutor. At noon, a sheik taught a lesson on the daily hadith, the words and deeds of the prophet Muhammad, which Wright then memorized. Later, the sheik questioned the students about the hadith.

After a dinner of beans, rice, okra and other vegetables, Wright continued his studies.

“This was not a place where you got to learn how to shoot a gun. Only the guards for the sheik had guns,” said Wright.

But he soon discovered that spies at the camp had notified the military that an American was there. Three soldiers with AK-47s showed up to take him into custody – without charges – and jailed him.

“I was the only American,” he said. “They just locked me up and gave no reason why.”

The next day, they transported him to Sana’a. Like his friends, Wright was blindfolded, questioned and thrown into Central Prison. He was assigned a cell with 15 other Muslims – from Egypt, Indonesia, Djibouti, Belgium, France and Saudi Arabia – all of whom had visas to study Islam.

“I was prepared for the worst. Maybe they’re going to kill me,” said Wright, who suspected one cellmate – chummy with the guards – of being a spy.

An elderly man from Saudi Arabia was found hanged in a cell.

“The inmates believed the guards hung him,” Wright said.

“The guards questioned me, and tried to say I wanted to go to Afghanistan, but I told them: ‘I don’t want to go to Afghanistan. I came to Yemen to study.’ ”

Christoph Wilcke, a Middle East expert at Human Rights Watch, said some students of religious studies drift into radical circles, such as John Walker Lindh, a California teen who studied Arabic in Yemen in 1998. Lindh is serving a 20-year federal sentence for being a member of Afghanistan’s Taliban army.

Eventually, Johnson, the U.S. legal attache, was able to negotiate Wright’s release. She provided him with a $1,000 airline ticket home.

But Yemeni soldiers treated him like a terrorist. His passport was stamped with a black mark, indicating that he could never re-enter Yemen.

He was handcuffed until he was on the plane. At a stop in Germany, a passenger told him: “You know terrorists don’t travel with luggage.”

“They called me a terrorist!” Wright said in disbelief. “I had nothing, no clothes, no jacket, just enough money for the bus to Philadelphia.”

Wright was in for a bigger shock when he got home.

Al-Amriykiy and Whittaker arrived at Newark’s international airport on Oct. 28, 2001. “I wanted to kiss the ground,” said Whittaker.

“I don’t want to leave the country at this point. Not anymore,” he added.

“I didn’t have time to kiss the ground,” said Al-Amriykiy. “I wanted to find the fastest way back to Philadelphia to get in my own house and my own bed.”

The two hopped in a taxi to Philadelphia – ironically, driven by a Muslim, who grew more horrified as they described their ordeal. When they arrived home, the cabbie gave them a reduced rate.

Al-Amriykiy’s first wife under Islamic custom, Zaynah Watkins, 49, tried to raise money for his release, but was shocked by the indifferent response.

“Muslims I was close to just brushed it off,” Al-Amriykiy added.

His second wife (he is legally married to neither), Tahira Groce, 29, cried and worried that her unborn child would never see his father.

“I was devastated,” said Groce. “The only person I wanted to be around was the other wife.”

When Wright arrived at JFK International Airport on Dec. 11, he was shivering from a blast of frigid air, while wearing a long, thin shirt called a khamis, pants and open sandals.

“The way he came home was so sad,” said Al-Amriykiy. “When I saw his face, he looked angry with the whole world. I knew how he felt.”

“We went to buy him a coat and made him feel welcome,” he added.

Later, Wright stopped to see his mother in Philadelphia. His stepfather opened the door and was taken aback.

The State Department had mistakenly notified his stepfather that Wright was dead – in Yemen.

Years after returning from Yemen, Wright and Al-Amriykiy were contacted by FBI agents.

FBI spokesman J.J. Klaver would neither confirm nor deny FBI contact with anyone.

But Klaver cited the bureau’s top two priorities: counterterrorism and protecting the U.S. from foreign intelligence operations and espionage.

“They wanted to question anyone [who went] to countries not friendly to America,” Wright said. He told the agents he was a Sulafi, who practices an early form of Sunni Islam, common at the time of Muhammad.

” ‘One thing we know about Sulafis,’ ” Wright recalled an agent saying. ” ‘You stick to the Quran and the Sunnah [Islamic law], but those other people . . . ”

Yemeni prison was not at all like America’s prisons with “three meals a day, and playing ball with everybody,” said Al-Amriykiy.

“There, innocent people are tortured and persecuted” and imprisoned for no reason.

“American prisons are like Beverly Hills,” says Wright, who is now studying to be a paramedic.

The nightmare shared by Al-Amriykiy, Whittaker and Wright in Yemen’s prison made them want to warn other Muslims fo the danger.

They even offered to speak at area mosques, but no one took them up on their offer.

“If you want to study Arabic or the Quran, you have to be sponsored by an Islamic school or religious scholar in the Middle East,” said Al-Amriykiy.

Here is a follow up: http://www.philly.com/dailynews/local/20090428_…

SubhanAllah. May Allah protect us from this situations and Muslims of the west must take notice – we must build our own institutions of learning, bring and raise our own scholars, bring the knowledge HOME.

why are they doing this to these innocent American Muslim Brothers

it is just sad seeing this in a Muslim country

as salamu alaikum,

Do you have any advice for Americans considering studying overseas, in terms of which countries are safe, the “do's and don'ts” of living abroad, etc.?

as sallamu alaikum wa rahmatullah

Inshaa Allah you are in the best of states.

May Allah give you good in this life and the next.

If one is going soley to learn arabic that can be done here, and many have done just that. If one's niyya is to learn the foundational principles of one's deen that can be done as well. Its from the sunna to get all the knowledge one can for one present location.

Barak Allah fikum

Abdul Latif Al-Amin

“YT: Do the foreign students in Dar al-Mustafa face any pressure from the government?

On the contrary we found a great deal of co-operation from those in positions of responsibility in the government. The talk of some about the Government putting pressure on foreign students of the sacred sciences is contrary to the truth. The only demand of the security services is that they do a check on the students to ensure they do not belong to any groups or ideologies that could be detrimental to Yemen .

The truth is that the government and people of Yemen will not accept Yemen, a country with a long history of producing balanced callers to Islam who were able to convince others to embrace Islam, be turned into a country which produces extremism and radicalism. There are some places in Yemen that taught Western students extremist views. This reflected badly on Yemen and its moderate schools when those students returned to their home countries carrying those views, and this of course is unacceptable. “

http://yementimes.com/article.shtml?i=1008&p=re…

Asalamu alaykum,

There are a number of things to be learned here:

1. These brother's love for the din and wanting to study is touching. The elderly gentlemen's desire to study is something to admire.

2. Our Philly brothers and sisters get very little respect, but I find them all over the Muslim world trying to study and raise their children as good Muslims. Agree with them or not, you have to give them mad respect.

3. American's are often targets of such security agencies that collect the information for agencies back home

4. The racism that exists in the East. I'll be honest when I say that White American Muslims are treated differently when found in similar situations

5. Building our own institutions in the West

6. The utter irresponsibility of those who call for hyper millitancy and hijrah when the live in such places. Instead of worrying about the West; seeking to destabilize our youth, the should worry about the taghut and oppressors in their own backyard.

SDW

Subhan-Allah! I have had my mind concentrated on Yemen for some time now to study, work and allow my teenage boys to study. And last night I made dua for the best; now this morning I read this article. Allahu Hamd. DH and I have a responsibility that must be fulfilled toward these boys of ours.

Brothers/Sisters what do you suggest?

SubhanAllah wAllahul Musta'aan. The racism overseas is appalling… I wonder if this would happen if they were white Muslims. Allah knows best.

I have longed to study in Tarim as well, though I'd have to study Arabic for a while before I can. But I know many people have gone abroad to study Islam but have a very difficult time readjusting when they return to America, Subhanallah.

They feel “stuck” or paralyzed because they do not find the baraka in time, the ease to study and stay away from fitna. it seems difficult to function, which is kinda scary… just one more reason why it seems smart to build our institutions HERE so ppl can learn and develop in a more organic, natural way, developing their character, habits and stuff while dealing with surroundings we can't easily escape.

It's just sad because the baraka and feeling of being in those places, with ppl of such high caliber, can't be duplicated.

as salamu alaykum wa rahmatullahi wa barkatuh

if anyone would like to go to tarim to study they should get in contact with the people at dar al mustafa first. they will sort out your iqama (residency permit) , housing etc. for you. we never felt any pressure from the govt. when we were there

brothers can study arabic there at badr institute.

it is difficult to adjust after being in a place like that but 9most people that come back from tarim are fine. they teach a balanced way of islam.

the lands of the Muslims are vast and each place has its own unique and special qualities. for those who traveling overseas is not an option they should be patient and use what we have here in the west.

May Allah help us all in our quest to draw closer to Him

duas please

wasalam

umm salih

Salaam,

I disagree with a-denver. I do believe that the barakah and the feeling of being in those places can be duplicated. It is our responsibility to establish institutions that can bring not only the academic rigor the parallels those abroad, but also the spiritual atmosphere as well. It is true that there is a sense of simplicity while studying abroad, but it is a matter of how you choose to live life. Studying Quran, no matter WHERE you are, is a beautiful and moving experience period.

Hmmm…do you experience the same clarity in the land of kufr that you do in the lands where the adhaan is heard five times per day? Lands where the remembrance of Allah azza wa Jalla are foremost on the minds of Muslims despite their shortcomings? Kindly inform us of a place where Al Islam is being practiced in the West without influences of kufr? Jazakumullahu khairan

Salam,

One of the things I like about this website is the balance it presents in the issues discussed on its forum. This is obviously a serious issue that everyone needs to be aware of and I can tell you of more horror stories I heard growing up in the so called “muslim” arabic world.

One reminder though. Please do not forget that the test the brothers have gone through, and Alhamdullillah their hearts were stabilized by the mercy of Allah, is a test that muslims go through regardless of where they are. The US and many other countries in the world do perform these kinds of unethical treatments and as they say in Arabic “Ma Khafi Kana Atham- what we don't know is even more/greater”. Just remember that these times we live in are a time of tests to our faith from both those who claim to be muslims and would lead you to hatred and extremism and those who would stick a label to you and persecute your faith.

Allahuma ya muthabit al quluba wal aqdam, thabbit qolobana ala dinik

Nomad78

The treatment these brothers received was disgusting and appalling but not surprising. I've been hearing about these things for years. From the tendency to many aarbs calling every black person they see abdi in Saudiyyah to black people being challenged to prove they're Muslim by taxi drivers in Egypt by reciting Al Fatihah.

This story should pause to those who have relinquished control of their thinking the others. Al-Amriykiy? Why would someone not an arab use that name tells alot about a person's self respect. No arab is the US would allow themselves be called Muhammad the Yemani or Hasan the Saudi but it's somehow “islamic” to call yourself by another culture's term.

Moreover, I must admit I'm humbled by Allah's blessings that I live in California. So I don't need to go abroad to study Islam when I have the Jamaat of Shehu Uthman dan Fodio in San Diego or Imam Luqman Ahmad in Sacramento or Shaykh Hamza & Shaykh Zaid at Zaytuna or even Khalid Abu El Fadl at UCLA.

We definitely need to build more institutions so all muslims in the US can be so fortunate as those in California .

“Al-Amriykiy? Why would someone not an arab use that name tells alot about a person's self respect”

I am sorry brother but this is a silly comment. We were five Ahmads in college and we went by Ahmed Ilfalastiniy, Illubnany, Ilmasri……..etc. Plus Salman, RA, is known as Al-Farisi.

Nomad78

Suhaib ar-Rumi

Salman ar-Farsi

Bilal ibn Ribah aka Bilal al-Habashi

Three companions, who grew up or who's family came from non-Muslim lands. It just tells us where one is from. There no value judgement attached.

You missed the point ! All the Ahmads you mentioned were arabs so it's natural to use an arab term for yourselves. As far as the Companions they all lived in arabia and spoke arabic! So why would they not use arabic term to refer to themselves in arabic speaking environment.

In an english speaking country there no reason for non- arabic speaking person to use an arabic term to refer to themselves when they don't live in arabic speaking environment.

It makes just as much sense as you being arab calling yourself by Chinese term. Now why would call yourself by a Chinese term? You don't live in a Chinese speaking environment and you 're not Chinese so what's point? There only reason for such behavior. One places more emphasis and respect for another culture than one's own….ie lack of self respect.

Bro…he did it because he wanted to. Even though, I'm not arab but I would use that cause I think it's cool.

There it is. Good explanation….. Hamza21 this is a losing 'battle' as long as people continue to only recognize the “Arabization” or better still….the “foreignization” of Islam – the terms….wow. Islam is everywhere wal-humdulillah. We need no more change our names than our shoes. We have to stop people's thinking that it is mandatory to change every aspect about their outer selves in order to be more “Muslim”.

I understand why people change their names, change their clothing style, start cooking lamb and rice solely when they used to cook pot roast. It is both a devaluation of the self, as well as a constant interrogation as to the validity of one's Islam – by other converts engaging in this radical change as well as foreign immigrants.

I should not have to explain to a immigrant Muslim that I am an American, daughter of an American, daughter or an American…….9th generation American, in order for them to believe that I am American; and no I am not Sudanese, Nigerian, or whatever country configuration they imagine in their heads. But when you have to deal with that – and in the country of your birth, it makes a person want to make their lives easier on themselves – especially when this is not a isolated incident but a continual occurrence.

Salam

Although this is a terrible story, can it really be used to support the fact that Hijrah is not obligatory? If we use these isolated stories to prove or points. Then why don't we use the everyday stories of Muslims living in the west who leave Islam, and are forever trapped in the ways of sin. People only hear about such stories “first hand” maybe once or twice in their life whereas we see Muslims losing their religion in the west everyday. These stories should not be presented as the norm because their are millions of people and not just Americans who have been living abroad for years and understand how to live amongst the people being responsible enough to know where and what they should be involved in. I would not believe that police would just go to an American in the fruit market for example on a random day and take an American and say ” come with use were going to put you in prison”.In most cases it is because Westerns are in places that cause suspicion. For example the Yemen Shakyh Muqbil and his tribe, who many American Salafi's go to for studying know that the Yemen government does not agree with any body who associates with them and even more so foreigners. If our modern day scholars are going to base their rulings on isolated events then the realm of “opinions” will differ on a daily bases. So what is the criteria for a valid opinion? When we look into the history of Islam we see that the scholars always insisted on hijrah throughout the centuries and it is seems that the “pro-western” scholars of today are the ones that seem to stand on their own in their opinions. If the scholars throughout the centuries said it was obligation and today's western scholars say “no” t because times have changed then why can't they make temporary marriage permissible since there is so much fornication going on? I think it's quite strange that are past scholars generally repeat the same thing and then modern day scholars excuse themselves from following what has been established and prove it with isolated stories. While we base our proofs on stories such as these we turn a blind eye to the reality that exist in the west or maybe it is because we are so accustomed to it now. i don't understand why there is this idea that because we are ''Westerns” that their is some version of Islam specifically for “us” so much that people ask for a rule and say “and what about for westerners?” I think that those who say hijrah is obligatory unconditionally ( poor or sick) is based emotion just like those who say that it is not obligatory unconditionally. The middle way is to say what has already been said and that is that it is obligatory but just like any other thing that is obligatory it applies to the one who has the ability to perform it.

Allahu Akbar!!! Your reward is with Allah azza wa Jalla!

salam,

Assuming that you are correct in that hijra is obligatory on us all, what is a suitable place to make hijra? The Muslim countries of today are not exactly Islamic, and often, we have more freedom to practice our religion in the United States. Additionally, if there are no Muslims in non-Muslims countries, who will make da'wah. In the past, the spread of Islam was facilitated through conquest and trade routes, both of which are nonexistent today. I find it most ironic when people who converted through da'wah (not talking about you in particular) in a non-Muslim country advocate hijra.

I disagree with you. The elderly gentleman has two wives, not legally married to both, they are not financially secure because they had to turn to the community to raise money, one child on the way. I am sorry i dont find his conduct touching, instead it is about a man running from his responsibility to go to the mountains of Yemen ( a halal little vacation). The two young guys might have been sold a romantic view of hijrah, but he should have known better.

Really Ali I would like to read this, but paragraphs please……No offense but your ideas are lost amongst the sea of overextending lines.

From the first point, this article was not “be[ing] used to support the fact that Hijrah is not obligatory;” rather, it is a warning to us Americans who go oblivious through our lives and who do realize the hazards of living in the “Muslim World.” We sit at home and talk about how we are mistreated by our government, but it is not until the stark reality of existence occurs before you really appreciate this place. Wa Allahu Akbar.

One is to be grateful in all their circumstances, and there is a great nimah in our country the United States, something we should be continuously grateful for and beseach Allah for his continual mercy for the place in which we live – despite the obvious fitna.

There are people who leave the dean, who loose their iman, who become sinful. Some of these people loose their way and do not know how, or are too proud to return to the Mercy of their Lord. Is this not same throughout this life, amongst human beings? Indeed you will not find fault with my statements.

It is unfortunate that what you saw from this article was an argument against hijra. Truly within this article many things can be gleamed that we should learn from.

1. State Department warnings are in place for a reason. Are we so ignorant and arrogant that we can disregard the climate, that when it is flooding we decide to go for a walk?

2. We are not free to “roam” the earth. Did it not occur to these men that they were “out of place,” and before deciding to explore the land they were in, they should have learned their environment first. If you are not from Crenshaw, or Oakland, or Brownsville, or the South Side of Chicago, or the back woods of North Carolina, you would not “roam;” why feel so free to do so in a foreign environment.

3. We have to take responsibility for our actions. If we decide to go study someplace, why take the world of someone else – and only 'one' someone else. Taking the easy way, is not always the best way.

4. There is trouble entering a place that requires bribery to function on a daily basis – enough said.

5. Muslims are human beings – we are finding more and more that it is not the “country” we should seek, but we must seek the person, or pockets of people that are still holding the standard of the Prophet in tact. We must remove the ideology of the “Muslim World” and replace it with finding the gems.

Example, Dar al-Mustafa and Dar al-Zahra. Now people who go to Yemen now, seek out a specific place. This

place has been reviewed and it has gained the trust of its students.

I apologize that I was unwilling to read the remainder of your comments, hopefully this has addressed your arguments and you will be satisfied.

I also apologize to anyone who may not understand the examples given in which to illustrate my points.

And Allah knows best

S.

I think you missed the point completely Leila. The touching part is that they went to seek knowledge and thats it.

You mean Mut'ah? Why would mut'ah be allowed when the Prophet forbade it? Besides there's Nikah Al Misyar. It's permissible but not advisable. Shaykh Suhaib spoke about this in beginning moments of Class 6.

http://www.virtualmosque.com/blog/online-class-not…

The brothers should have gone to Dar al-Mustafa, Hydrawmaut, Yemen.

Thats sad A .whittaker is my 1year old son dad that he is not takeing care of.

What Tina? This is not true my husband does not have children.